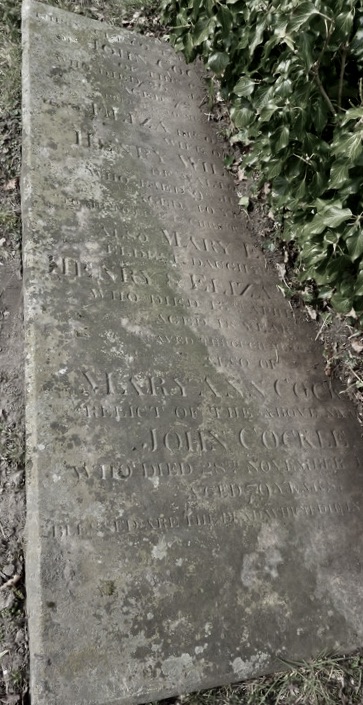

The headstone records members of John Cockle’s family in Trimley St. Martin Churchyard. (Entrance to a vault.)

The headstone records members of John Cockle’s family in Trimley St. Martin Churchyard. (Entrance to a vault.)

Some weeks ago, I was reading a newspaper, ‘The Suffolk Chronicle’, for 17th May 1817. A small report containing the skimpiest of information caught my eye:

“COMMITMENTS. – To the County Gaol, in this town, James Burroughs and Wm Wright (by the Rev. John Edgar) charged with stealing about three coombs of wheat, the property of John Cockle, of Trimley, Surgeon.”

Several facts in this sentence captured my attention, not least because I had come across John Cockle before when I was investigating the Trimley St. Martin Inclosure Award of 1807. I had followed up this encounter with some research into his life and already knew he lived until 20th January 1849 and was buried in Trimley St. Martin Churchyard. Reading his Will, proved on 13th March 1849, it’s clear he was a man of means and some substance, for he had bequeathed £1,000[1] to each of his eight grandchildren. This translates to £128,011.24 in 2019 monetary value. Further small details emerged as I conducted my research and inevitably, so did more questions. One thing followed another and the small pieces of information opened a window into the lives of the worthy and less worthy inhabitants of Trimley St. Martin in 1817.

The chain of events which adversely affected Mr. John Cockle, Surgeon of Trimley St. Martin, began which two years earlier on the fifth of April 1815. It has to be said he was not aware of this and nor did it shorten his life expectancy in any way. However, from the middle of 1815 to 1817, in common with the population of North America and Europe, he was indirectly affected by the side effects from the eruption of a volcano in Indonesia.

The catastrophic explosion of Mount Tambora began on April 5th 1815, spewing volcanic matter into the air, causing it to fall on East Java the next day. The activity continued, increasing in intensity until on the tenth April 1815, when the most violent eruption ever recorded in human history, finally exploded. Such was the violence and ferocity of the event it could be heard a thousand miles away on the island of Sumatra; the impact on the immediate locality was complete devastation. For the twelve thousand population of Tambora and ‘Peccate’, another town in its vicinity, the result was not just decimation; the entire area was reduced to a population of just twenty-six people. The town of Banyuwanga (or Bannicanga) in Java, a hundred and fifty miles away, was covered in ash to a depth of eight inches. The eruption was approximately four times that of Krakatoa in 1883 and its impact was not confined simply to the Indonesian islands. The explosions caused clouds of gases and ash to be propelled into the stratosphere, where they then spread across the globe affecting the northern hemisphere. It was to be a long, slow fall out, which initially resulted in famine in parts of Indonesia and tellingly, spectacular sunsets in Paris and other parts of Europe.

Such was the slow pace at which news travelled from the Far East it took ‘The Bury and Norwich Post’ over a year before they reported the ‘Dreadful Explosion’ on the 15th May 1816[2]:

‘…far exceeding in the extent of its effects, any of Vesuvius, Aetna or Hekla…(and) the darkness produced by the quantity of dust in the air was terrific…’.

It is inconceivable to think anyone at the time connected the failure of the harvests in 1816 during what became known as ‘The Year without Summer’, with the ferocity and extent of the Tambora explosion in 1815. It was at the beginning of a long period of economic hardship for many but particularly for the Agricultural Labourer. The immediate legacy was the impact on the weather on crops and harvests in 1816. People in the northern hemisphere were to suffer crop failure, starvation and typhus. These conditions, combined with the demobilisation of the militia following the end Napoleonic Wars, saw many soldiers begin their long journey home across Europe. Those from Great Britain arrived home to find themselves in the middle of a food crisis, which dated back to 1813.

The harvests between 1813 and 1815 had been poor caused by an El Niño[3] event, not recognised at the time. The huge numbers of ex-soldiers combined with the wide spread crop failure, placed a significant burden on their communities and counties at large. In 1816, the Eastern seaboard in America saw an early spring subjected to plunging temperatures and in June, July and August there were further heavy snowfalls and frosts which combined to kill off crops. In Europe, between April and September, rain deluges of Biblical proportions lay waste to cultivated land. It has been stated that wheat yield in 1816 were up to 75% less than normal[4] and on 20th July, ‘The Times’ reported:

“The hay towards the southern counties has been so much injured by the incessant rains that the only alternative left to the proprietor is to convert it in to dung or manure. The clover likewise has sustained equal damage with the hay and has been made same use of. This unexpected visitation from Heaven, added to the severe distress to which the country is otherwise reduced…it is now expected… corn will also be seriously injured by the heavy rains which have fallen…We may add the weather continues bad all over the Continent.”

Set against the backdrop of a failed harvest in 1816, it doesn’t take too much imagination to realise the effect this had on the value of wheat. In the first instance, scarcity raised its value. Any farmer or landowner who had wheat in his barns held an inflated source of income. The failure of the American Crops also impacted negatively in Great Britain, as this country imported their softer wheat variety, whilst exporting much of the harder home grown variety. Between 1815 and 1817, bread more than doubled in price[5].

By 1817, nearly two years after the eruption of Mount Tambora and following on from the widespread cold weather, ‘The Ipswich Journal’ on the 3rd May 1817 reported that:

“Of the appearance of wheat generally, the reports are far from favourable; those sown at the regular autumnal season are said to wear the worst aspect, being thinly planted, yellow and sickly, greatly injured by the wire-worm and slug, to such a degree in some parts, that the remains have been ploughed up, and the land re-sown with barley…The fruit trees and gardens have sustained considerable damage from the cold winds and severe nights…”

A local indicator of how bad conditions were for the labouring poor in 1817 may be found in the Trimley St. Mary Town Book (1782 – 1858)[6]. £101/8/7[7] was distributed or ‘disbursed’ to the poor between Easter and Midsummer. Of this sum, £25-16-3d[8] alone was paid out between July 21st and July 31st 1817. Note, this was during a summer month, when work should have been plentiful for the agricultural labourer. The local charities were normally distributed in January, when wintry conditions prevented the labourers from working.

There was of course, one other factor which played alongside these natural disasters: The Corn Laws. These favoured the farmers because the laws kept foreign corn out of Great Britain, which in turn meant the price of Corn could be controlled by the Farmers. Prices became artificially high and therefore unaffordable for many lowly paid agricultural workers, who had helped to produce it in the first place. Hunger and starvation dominated the lives of the poor until the law was repealed in 1846.

These circumstances go a long way to explaining what happened to John Cockle of Trimley St. Martin in May 1817. His profession was as a Surgeon but like many other comfortably situated country gentlemen, he diversified his income streams. He held several portions of land in both Trimley St. Martin and Kirton and it’s possible to locate these on the 1807 Inclosure Award and Map. The majority of his land in Trimley is in the area formerly known as Little Street Farm: Howlett Way now cuts through it on the way to the A14. The land in Kirton lay between Kirton Road and Back Road. It may be that John Cockle acquired other portions of land after Enclosure. Certainly, by the time the Kirton Tithe Map was drawn up in 1839, he held five acres in the village; the Trimley St Martin Tithe Map of 1840, records Cockle liable for twenty eight acres in Trimley St. Martin. However, in 1817 it is assumed his land was the same as at the time of Enclosure. His wheat crops in 1816, despite the terrible weather conditions across the country had yielded at least three coombs.

Land held by John Cockle in Trimley St. Martin, taken from the 1807 Inclosure Map with modern street names.

Land held by John Cockle in Trimley St. Martin, taken from the 1807 Inclosure Map with modern street names.

To return to the news item in ‘The Ipswich Chronicle’ of 3rd May 1817. Two men, James Burroughs and William Wright were arrested and marched off to prison for stealing three coombs of wheat[9] . On the 19th May, ‘The Bury and Norwich Post’ reported the two had been committed to Ipswich Goal by the Rev. John Edgar, presumably to await their trial. As a point of interest, the Rev. Edgar[10] had been appointed Vicar of Falkenham in 1796; in 1813 he was appointed as Stipendiary Curate to Kirton; in 1820 he became Rector of Kirton. It may be assumed he had good connections with the Trimley and Kirton area and the local landowners. At this point John Cockle could choose whether to prosecute or not. As a member of the Colneis Association “… for prosecuting Horse Stealers, Felons, etc..”, he had a form of insurance to pay for the prosecution. The Felons had no redress to any form of legal support, given their supposed impoverished status.

The case finally came to trial until Wednesday 17th July 1817 when three men appeared at the Woodbridge Quarter Sessions. The Ipswich Journal for the 19th July briefly recounted the story:

“James Burroughs, Robt. Wright and William Wright, were indicted for having, on 1st May last, stolen 6 bushels[11] of wheat from out of a barn at Trimley St. Martin, the property of Mr. John Cockle: in this barn Burroughs and Robt. Wright, who are servants to prosecutor, had been working the day preceding the robbery. Burroughs was Head Man and confidential servant to Mr Cockle; Burroughs pleaded not guilty, and Robt. and William Wright guilty: Burroughs was sentenced to 7 years transportation Robert Wright 18 months imprisonment, William Wright 6 months imprisonment.”

The Woodbridge Sessions[12] register in Suffolk Record Office, more accurately reports the details. The felons appeared before Charles Davy, Clerk; The Hon. and Rev. Frederick Hotham, Clerk; William Carther, Esq;. Edward Moor, Esq.; George Turner, Clerk; John Edgar, Clerk; William Brown, Clerk; Samuel Kilderbee D.D. (Kilderbee was a close associate of George Nassau, Trimley St. Martin’s Lord of the Manor, at that time.)

The entry in the Woodbridge Sessions book reads as follows:

Robert Wright and William Wright Severally pleading Guilty to the Indictments for Grand Larceny are several ordered to pay a fine of one shilling each and to be imprisoned in the County Gaol for the respective terms following (that is to say) the said Robert Wright for the term of eighteen months and the said William Wright for the space of six months.

James Burrows

Convicted of Grand Larceny is ordered to be transported beyond the Seas for the term of Seven Years to such place as his Majesty shall by and will with the advice of his Privy Council think fit to appoint pursuant to the matter. (p.169)

John Cockle expences prosecuting James Burrows – felony. (p.171)

Transportation was a heavy penalty for James but did it actually happen? It may be he compounded his felonious mistake by pleading ‘Not Guilty’. The tacit implication of the sentences is that he was the ring leader and the others were pulled along in his wake. My inconclusive investigations suggested there may be a familial link between the three men for a James Wright Burroughs married a Charlotte Osborn in 1813. This is just supposition and in truth, James’s life disappears from view in 1817. Did he die? Is there a misspelling of his name which baffles the researcher? I don’t know. He remains vanished until future investigation reveals him. This applies equally to Robert and William Wright in their turn. What became of their futures after their prison sentences? Did they return to working in the agricultural environment? Again, there is no immediate answer to hand. Rightly or wrongly, who would happily employ those with a criminal past in such times?

Action had been taken; the Felons had been accused, prosecuted and imprisoned. Did Mr. Cockle receive any remuneration? Probably not but a message had been sent out to any further would-be miscreants. For John Cockle, life resumed its normal pace; he was sufficiently monied to stand the loss of his wheat. The volcanic eruption which had upset the weather conditions was probably only impacted on the outer fringes of his consciousness. However, protecting what was his was most assuredly not; it remained a matter of prime importance. Such was Cockle’s understanding of the necessity to protect his investments, he continued to maintain his membership of the Colneis Association and of this organisation, you may read more at:

There is a curious footnote to John Cockle’s life. In 1987[13`] builders were working on Trimley St. Martin’s south door. As they started digging the footings an eight feet square brick vault was revealed. Inside were the remains of four bodies together with the remains of wooden coffins and brass and tin name plates. The bodies were those of John Cockle, his wife, daughter and grand-daughter. The Rev. Christopher Leffler issued public notices asking any surviving family members to contact him but none did. The remains of the bodies were buried in the churchyard. The existence of such a vault indicated wealth and some privilege.

*************************************************************************************

If you have any comments or would like to be part of this Trimley St. Martin project, please contact me at:

trimleystmartinrecorder@gmail.com

LR 28/02/2020 Revised 5/5/2022

*************************************************************************************

[1] England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384 – 1858 for John Cockle. Prob11: Will Registers 1848-1849 Piece 2089: Vol 4, Quire Numbers 151-200 (1849)

[2] The Bury and Norwich Post 15th May 1816

[3] https://academic.oup.com/jn/article/132/7/2092S/4687313

[4] https://watermark.silverchair.com/4w07020s2092.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAmEwggJdBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggJOMIICSgIBADCCAkMGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQM2oC9C_1M5EJDK8y4AgEQgIICFFy4rATvSRqwuzpHX6jOMkRh3HvBX9gAZWxHYGCHfKLsJ7w2L7sTLbzNrXYG7R70_InZTE3JdPzs7ZexIC6ZP0xoEqxI6zBhQzdNIu0Hif4xqeprWSWfiyKqS1ik8r1zIRoLv39Y_d1z8THfhyDbAhZpQo9uFQ6sow_E9MGB7slPAWEfyMRzKG1HCI0Hpg41LVIV5nKrgRfhSaxf3s_y-7LZsrPyWEweIEDgcK0Ml_S_bjm1n021b0GDi-kgRNZAUhFY0vnzPY5FhfwoglAmrTmV85v4gJ8uUjUfgEvkv0eAPxi9Nr3DgMyIz0ssHJ16oFaylTsgRuJYFKvbHUOH7-

[5} The Economic Crisis of 1816-1817 and its social and political consequences John D. Post The Journal of Economic History Vol. 30 No.1 The tasks of economic history.(Mar. 1970) pp.248-250

[6] The account of the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Parish of Trimley St. Mary (1782 0 1858) FC49/A3/1 Suffolk Record Office

[7] Using the Bank of England Inflation calculator this would be about £8,717.37 in 2019 money.

[8] Using the Bank of England Inflation calculator this would be about £2,179.07 in 2019 money.

[9] At this point you may be asking the question: what is a coomb and what was it worth? ‘The Norfolk Quarterly report’ section in the August 1817 edition of the ‘The Farmer’s Magazine’, informed the reader that the price of a Coomb had been at one point 74/- (or £293.70 in 2019[9]) but was now not worth much more than 56/- (or £237.50 in 2019 money) per Winchester coomb. According to the Metric Views site[9], a Beccles Coomb was 240 lb. Just to confuse the reader a little further, a coomb was also known as a strike. For the sake of calculation, I have temporarily twinned Beccles and Winchester measurements and estimate three coombs would weigh 720 lb, although this is only a very rough guess.

[10] The Rev. John Edgar (1761 – 1821)

[11] Two bushels were the equivalent of one strike or a coomb https://www.britannica.com/science/bushel

[12] B/105/2/58 Woodbridge Sessions General Quarter Sessions pages 169 – 170 16th July 1817

[13] East Anglian Daily Times. 1987

Dear Liz

I researched the land on which my house is located in the Tithe Map of 1839 at the SRO. This is now in Old Kirton Road but would have been in Drabs Land then. I think that my house is located on what was field site 21. This is shown with the landowner as Rev Samuel Kilderbee because this was glebe land. The occupier was John Cockle paying £10.12s 0d for all the land he rented. Field 21 was arable land of size 3 acres 1 rod and 31 perches. I noted that John Cockle was a landowner on adjacent sites. I think that he might have been the owner of the house Little Street Farm – it is shown opposite the junction of Gun Lane.

I did not think that he could be such a wealthy man as set out in his will. I thought that he would be what would nowadays be considered a small farmer.

Best regards

Lorna

LikeLike

Hello Lorna. Like you I was surprised at John Cockle’s wealth. I believe he married in Amanda Weeding in 1802 (Weeding is also on thee 1807 Inclosure map) I suppose he had something of a monopoly, probably because is likely to have been the main Surgeon in Trimley and district, as well farming land. I will have to re-visit the Tithe map at some point re Cockle’s house. I’ll show you the Will at some point as it makes for interesting reading. The family came from Woodbridge.

Re. the roads. Yes, Drab’s Lane! I marked the hand drawn map with modern names for fear of further confusion. The Kilderbees were pre-eminent, not least because of their very close connections with George Nassau, who presented the Inclosure Act.

Thank you for your useful comments. Liz

LikeLike