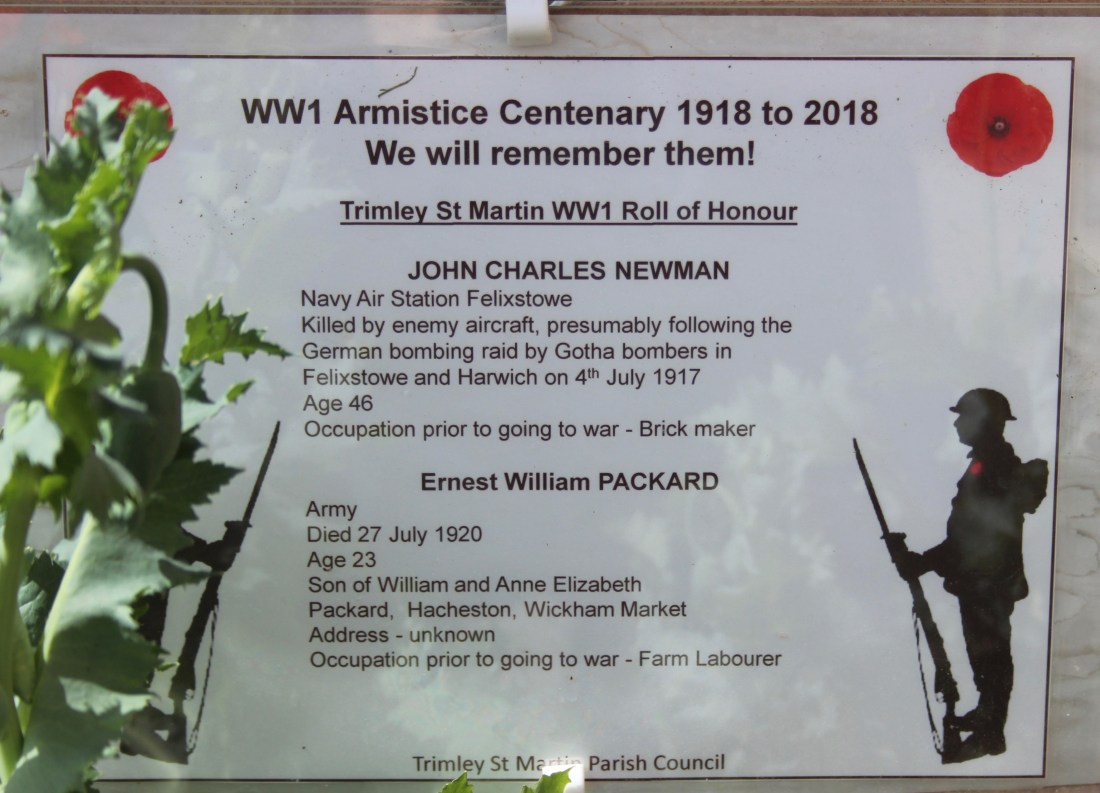

Part of the Poppy Cascade, St. Martin’s Church October – November 2018

Part of the Poppy Cascade, St. Martin’s Church October – November 2018

Last year the annual Remembrance Day commemorations focused upon the centenary of the cessation of First World War’s hostilities. Trimley St. Martin chose to recall the men who were called upon to respond to their country either through choice or conscription. Poppies were evident around the village in the Summer and during October and November 2018, the parish church tower supported a magnificent cascade of poppies. This year, 2019, the national services will once again be held in a manner that has become familiar to us. However, it is perhaps worthy of note that it is one hundred years since the inauguration of the ceremony and the first occasion had many differences

The two minute silence was originally called ‘The Great Silence’, ‘The Great Tribute’ or ‘The Great Hush’ and whilst it may have lacked the exacting military precision of subsequent years, it was the first sorrowful moment of national unification and in many ways, perhaps the most moving as an affected country recalled their own, all too recent losses. The ’Silence’ was observed throughout the British Empire and widely reported in the majority of the national and provincial newspapers. In Great Britain the solemn focal point then as now, was the Cenotaph in Whitehall. A short film exists showing a packed Whitehall where men cluster around the memorial, removing their hats when the very first Silence fell upon them. A weighty wreath was born aloft by people pushing through the crowd to lay it in front of the War Memorial. The crowd appears to consist almost entirely of men, although doubtless women were present. At the time absent parties might have read about the ceremony in the newspapers; today we can all view the mute, moving images[1] taken in front of the hastily constructed Cenotaph, then a ‘mock up’ of timber and canvas. The permanent Portland stone façade did not appear until 1920.

The deadly effects of the War did not always manifest themselves immediately and many of those who returned were not always long lived. This year, 2019, I have chosen to reflect upon the short life of Ernest William Packard, whose parents lived in Trimley St. Martin. My choice came about as the result of some correspondence I received last November from one of his twenty first century relatives, Giles Colchester, asking if I had any information about Ernest. I turned to Barbara Shout’s excellent work, ‘In memory of the Trimley Villages’ Fallen’, which is deposited in Suffolk Record Office. Unfortunately, the short answer was no. The only details she had managed to locate were the book ends of life; his birth and death with Census and General Register Entry pages between them. It was a combination of the lack of details and Giles’s email enquiry which highlighted Ernest’s importance. His short life was the fate of thousands of others engaged in the War and indeed, many other wars throughout history.

Ernest William was known as William by the time of the 1901 Census and this is how I will refer to him. Giles Colchester supplemented Barbara’s information with the very few details he had located. Uniting my own skimpy sources with theirs reveals the following story.

William’s parents were William and Annie Packard. According to both the 1901[2] and 1911[3] Census, his father was born in Framlingham in 1876 and his mother was born in Wilby in 187, about seven miles to the north. During the course of her life Annie was to travel nearly fifty miles from her birthplace and William forty before they reached Trimley, a testament to the necessity of moving to ensure employment. In 1901 William’s father was working as foundry labourer but this had altered by 1911 when he was working as a Horseman on a farm in Hacheston as was his son, William. Both father and son were part of the enormous labouring body who were fundamental to agricultural and industrial communities.

William was born in 1897 in Sweffling, part of the Hundred and Civil Registration District of Plomesgate. He appears to be the oldest of his nine siblings: Elsie Violet; Alice Florence; Ethel Annie; Frederick George; Thomas Charles; Ann Elizabeth, Constance Maud and Mildred Gertrude. His parents were William and Ann Elizabeth Packard. In 1911 he was living near the School in Hacheston although by then he had completed his education at Cransford Primary and Heveningham Voluntary Primary Schools[4]. His employment was as a farm labourer and doubtless he would have been involved with working on the land from an early age. During the late Victorian and Edwardian period, the school holidays invariably encompassed the whole of August when the harvest was gathered in. Similarly, there were periods during the Autumn term when school log books note the absence of children when they might be off school gathering acorns. Why acorns? To feed the family pig. It seems reasonable to speculate these activities were part of young William’s childhood.

On the 4th August 1914, William’s life along with millions of others, changed following the declaration of War. Overnight, the immediate response by the British government was the appointment of Field-Marshall Lord Kitchener as Secretary of State for War. One of his first acts was to increase the number of soldiers through promoting the enlistment of Volunteers[5] There was a huge surge of patriotic response and between 4th August and 12th September 1914, 478,893 men stepped forward to offer their services, an unprecedented figure. The numbers never reached quite the same peak but the necessity for able bodied men was such that by 27th January 1916, the first Military Service Act introduced conscription. There is no way of knowing how or when William responded to the need for soldiers as his military papers, like many others were lost when an incendiary bomb caused a fire in the War Office in September 1940. Approximately two thirds of the six and half million First World War records for non-commissioned officers and the ranks were destroyed. Those which survived often provide good career details but William’s are gone. Therefore, there is an almost complete absence about his military career and what follows is largely speculative.

Barbara’s information says the following:

“Does not appear on the CWGC site[6] Wrongly identified on the Roll of Honour. They have identified Ernest William by name but the detailing is for his relative Walter E. Packard D.C.M. They both have the same Great, Great grandmother…”

Giles Colchester suggested that he may have served in the Army Corps as a driver [7]when he referred to the Medal Card details from the National Archives. Part of the difficulty is the card simply refers to a William Packard and provides no further details: no next of kin, enrolment or promotion information. The same name and regimental number, T3/026778 appears in the R.A.S.C. Medal Book [8] dated February 1920, Again, because the soldier is described as a Driver, it is perhaps possible to make some speculative guesses as to whether this is the William Packard who died in Trimley St. Martin on the 27th July 1920.

Firstly, the R.A.S.C. was the Royal Army Service Corps. It was the responsibility of the Corps to provision the Army with all necessary supplies of food, ammunition, clothing et al. The Imperial War Museum holds one of the R.A.S.C. recruitment posters [9]which calls for ‘Men accustomed to horses’ because despite railways and motorised vehicles, horses were essential to the provisioning of the army. It has been estimated in excess of approximately eight million horses, mules or donkeys were killed during the First World War. Men who knew how to handle horses were a valuable commodity and it might be that William chose to join the R.A.S.C. because he also had experience dealing with them. The title Driver applied to both motorised and horse drawn vehicles. Within a few weeks from the outbreak of war over 120,000 horses were requisitioned [10] Secondly, Giles Colchester sent me the image of a photograph which he located on the Internet. Because of copyright issues I don’t have permission to reproduce it here. He informed me it purported to be of William Packard and his two sisters, Elsie and Alice. In the photograph two women are seated flanking a standing man dressed in standard Army uniform. There is no obviously distinguishing but slung diagonally over the man’s arm is a bandolier used for storing ammunition.

Thirdly, the address on William’s death certificate, which cites his occupation as Farm Labourer and Ex-Army, is 2 Boat Cottages. Boat House Cottages are on the High Road leading out of Trimley St. Martin. In 1920, approximately half a mile away on the left, a small lane led to Morston Hall. At the time, the farmer Mr. Arthur Pratt, was internationally famous for his prize Suffolk Horses. His name appears in many agricultural journals of the day, for example, ‘The Agricultural Gazette’ [11] for 5th July 1915 records some of his successes at the Royal Nottingham Show and makes specific note of the decreased number of Suffolk Horses present. Fourthly, the 1911 Census gives William’s father’s occupation as ‘Horseman on Farm’ in Hacheston. Although we don’t know when his father moved to Trimley, it could be he was working for Mr. Pratt. It is equally possible William himself had a good working experience of horses.

Cautiously piecing these highly speculative pieces of information together it might be conceivable that the medal roll entry for a William Packard is the correct entry for the man whose name appears on the War Memorial in Trimley St. Martin Churchyard.

Top Image: Trimley St. Martin War Memorial. Middle image: Trimley st. Martin War Memorial. Lower image: Ernest William PACKARD.

What happened after the War? Without knowing exactly when, it is clear William was demobilised and home by the summer of 1920. He was not to live for long as we can see less than a year separates the Armistice and his death. The death certificate bleakly records the causes of his death, primarily Pulmonary Tuberculosis of an uncertain duration and a secondary cause of Tuberculosis Meningitis. It is quite possible although not definite, William acquired Tuberculosis at the Battlefields of Western France. In England and Wales, the incidence of tuberculosis was 135/100,000 in 1914 and 170/10,000 in 1918. Infection and war appear to be close allies when it comes to human mortality. The symptoms of Tuberculous Meningitis make for grim reading: low-grade fever, malaise, weight loss over a one to two week period vomiting, confusion, coma and increased vomiting[12]. For William, these symptoms lasted a fortnight. His death was reported by his mother Annie, on the same day as his death in 2 Boat Cottages, Trimley St. Martin. Barbara Shouts records his burial in Trimley Graveyard and his name is inscribed on the War Memorial. And that is probably the sum of all we currently know about (Ernest) William Packard but as mentioned at the beginning, like millions of others he took part in the War which was supposed to end all wars [13]. and like many of those millions, his details are lost in time. We don’t know if he had a sweetheart or fiancée nor if he suffered from what we now call Post-traumatic Stress Syndrome (P.T.S.D.) However long he served, especially if he suffered from any form of mental or physical illness, he contributed to what we have to assume he believed in. Given the increased physical illness as a result of trench conditions, my own feeling is his death was caused because of the shocking conditions of the Battlefields but that is only my speculation. Despite the scant details of his life, he deserves recognition and remembrance, for as a friend reminded me,

‘Lest we forget.’

*************************************************************************************

If you have any comments or would like to be part of this Trimley St. Martin project, please contact me at:

trimleystmartinrecorder@gmail.com

LR 25/10/2019

*************************************************************************************

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxK56magHxE

[2]Census 1901 RG13 1791 34 Page 10

[3]Census 1911 RG14 PN10918 RG78PN590 RD215 SD2 ED1 SN2

[4] Ipswich Records Office National School Admission Registers & Log-Books Archive ref 358/5

[5] https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/28944

[6] Commonwealth War Graves Commission – https://www.cwgc.org

[7] WW1 medal card under the name William Packard Regt No T3/026778

[8] WWI Service Medal and Award Rolls; Class: WO 329; Piece Number: 1970 p.32

[9] https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/voluntary-recruiting

[10] https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/british-army-horses-during-first-world-war

[13] Attributed to H.G. Wells.